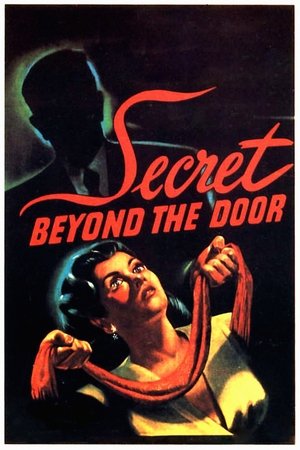

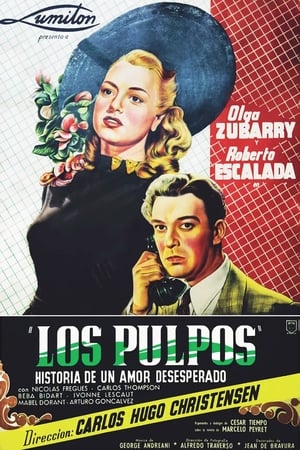

Overview

A dark personal secret drives a young woman to use every man she encounters.

Reviews

John Brahm’s The Locket (1946), or “What Nancy Wanted”

Written by Wheeler Winston Dixon

There are certainly any number of labyrinthianly complicated noirs, but nothing can quite prepare the viewer for the experience of watching John Brahm’s The Locket (1946), famous for its “flashback within a flashback within a flashback” structure, perhaps the most convoluted narrative in the history of noir. The plot itself is relatively simple: Nancy (Laraine Day) is a kleptomaniac, driven to steal anything that strikes her fancy (the original title of the film was “What Nancy Wanted”). Nancy’s compulsion springs from a childhood incident, in which she was given a locket as birthday gift, which was then taken away from her by the cruel Mrs. Willis (Katherine Emery), her mother’s employer. When the locket goes missing, Nancy is suspected of having stolen it to recover the trinket for herself. Although it is later discovered that the locket simply fell in the hem of a garment, Nancy is never truly exonerated. Now, twenty years later, Nancy is poised to marry John Willis (Gene Raymond), and thus regain admission to the household she was banished from as a child; Mrs. Willis does not recognize Nancy, having only known her as a child (played by Sharyn Moffet).

But within this seemingly straightforward narrative, there are numerous obstacles. The film itself begins on the day of Nancy’s wedding to John Willis. Just as the ceremony is about to begin, psychiatrist Dr. Harry Blair (Brian Aherne) breaks in demanding to see John. Dr. Blair, it turns out, was one of Nancy’s former husbands; Blair knows that Nancy is insane, and pleads with Willis not to marry her. As Blair recounts the tale of his marriage with Nancy in a flashback voiceover, he unfolds the tale of another of Nancy’s husbands, the late Norman Clyde (Robert Mitchum), a moody artist who ultimately committed suicide because of Nancy’s compulsive thefts, and her participation in a murder. All this unfolds in reverse, back to Nancy’s childhood and the incident with the locket, and then reverses to end in the present, where the still doubting John Willis, having heard Mr. Blair’s tale, confronts Nancy, who predictably denies everything.

Only Nancy’s collapse at the altar, brought on by Mrs. Willis’s “re-gift” of the locket Nancy briefly had as a child, saves John Willis from a similar marital fate. As The Locket ends, Nancy is taken off to an asylum ostensibly for a cure, but the camera remains within the gloomy precincts of the Willis family’s gloomy Fifth Avenue mansion. What has transpired has left a mark not only on Nancy, but all who knew her, and even Dr. Blair’s supposed skill as a psychiatrist is useful only after the fact. For most of the film, Nancy’s mania eludes detection, and everyone who discovers her secret is summarily destroyed. Thus, all surfaces are suspect, all appearances deceiving, and nothing is to be taken at face value, especially protestations of innocence.

Director John Brahm keeps a firm hand on the proceedings, and effectively stages The Locket so that most of it happens at night, on claustrophobic studio sets. Mitchum, a rising star at the time, is oddly convincing as Norman Clyde, a Bohemian artist with attitude to spare, and Nicholas Musuraca’s moody lighting leaves the characters, and the viewer, in a state of continual confusion and suspense. Most intriguing, of course, is the triple-flashback structure of the film, which brings into question the reliability of the film’s narrative. When Dr. Blair bursts in on John Willis and begins his recital of Nancy’s crimes, Blair’s flashback contains Norman Clyde’s reminiscences, which in turn contain Nancy’s own memories of her childhood, as told to Norman, containing the incident of the locket.

Thus, we have only Nancy’s word, through Norman, and then through Dr. Blair, that any of this is really true, and yet we unquestionably believe in the veracity of all three statements. Why? The entire story is so fantastic that one can understand John Willis’s lack of trust in Blair’s accusations; Nancy seems like a “nice girl.” The failed wedding that climaxes the film is proof enough of Nancy’s affliction, but are all the details of her illness quite correct? For this, we have only the word of three narratives that enfold each other like miniature Chinese boxes, refusing to give up their secrets, opening only when the proper pressure is applied to the correct location.

The world of The Locket is one of absolute doom and betrayal. The relationship you thought would last forever is doomed. Your friends don’t believe you. The police don’t believe you. You can’t even trust yourself; indeed, you are your own worst enemy. Powerless before the forces of fate, which have once again capriciously decided to deal you a new, much more unpleasant future from the bottom of the deck, you simply have to take it on the chin and hope for the best. The world of The Locket is the domestic sphere in peril, in collapse, existing outside the normative values of postwar society, values that are themselves constantly in a state of flux. The family unit is constantly celebrated in the dominant media as the ideal state of social existence, but is it, when so much is at risk, and so much is unexplained? For Nancy in The Locket, the answer is a resounding no. http://www.noiroftheweek.com/2009/04/locket-1946.html

Don't tell me your conscience is bothering you?

The locket is directed by John Brahm and based on a screenplay written by Sheridan Gibney, which in turn is adapted from the story "What Nancy Wanted" written by Norma Barzman. It stars Laraine Day, Brian Aherne, Robert Mitchum and Gene Raymond. Music is by Roy Webb and cinematography by Nicholas Musuraca.

Story tells of how a bride to be, who as a child was traumatised by a false charge of stealing, grows up to badly affect the men who wander into her life.

"You don't know the truth from lies, you are just a love sick quack"

A psychological melodrama with film noir flecks, The Locket turns out to be a most intriguing picture. Director Brahm brings into the production not only his baroque know how, where his Germanic keen eye for mood is so evident in films like The Lodger and Hangover Square, but also a dizzying array of flashbacks in a collage of psychological murkiness. Structured as it is, film can be disorientating if one isn't giving the film the undivided attention it needs. But for those all in with it, it delivers rewards a plenty, even if some daft touches stop it from being an essential picture for the genre seeker. Essentially the film is a case study of one young female mind deeply affected to the point that it has great implications on those who become involved with her.

Story raises some queries about the treatment of mental health patients, and their place in society, while some of the characterisations have good dramatic worth. Sheridan Gibney does a very good job with the screenplay, the tricky subject is given some thoughtful consideration whilst toying with the audience's loyalties about possible femme fatale, Nancy (Day), the ambivalence of which makes the ending from a writing standpoint far better than it probably has any right to be. Credit is due to Brahm, then, for bringing it home safely after employing such a tricky narrative device, it's far from being up with his best work, but it does showcase what a talent the German émigré was - the visual grab of the finale a case in point.

Of the cast it's the very pretty Laraine Day (latterly of I Married a Communist) who shines in a tricky role, while there's a nice stern performance in the support slots from Katherine Emery as Mrs. Mills. Mitchum was yet to find his acting marker (which would come the following year in Out of the Past and Crossfire), and here he's a touch miscast and gets by on presence alone - with his character getting one of the films' duffer leaps in logic moments, literally! and Aherne is passable and easy to listen to, but never really convinces as a psychiatrist. Musuraca photographs in suitable black and white shadowy tones, but like Brahm and Mitchum, this is far from the upper echelons of his best work.

If you can get past some daft touches and crucially pay attention, The Locket is well worth the time spent with it. 7/10

85 min

85 min

6.321

6.321

1946

1946

USA

USA

Steve wrote:

Steve wrote: